Berkeley student throws cold water on ‘monster’ black hole discovery

Sometimes, a blockbuster discovery is just too good to be true. UC Berkeley graduate student astronomer Kareem El-Badry knows that all too well — he just shot one down.

El-Badry studies unusual binary star systems in which one of the two stars orbiting each other explodes as a supernova and turns into a black hole. But he was surprised when, on Nov. 27, the day before Thanksgiving, Chinese astronomers reported such a system with a black hole that was astoundingly large: 70 times the mass of our sun.

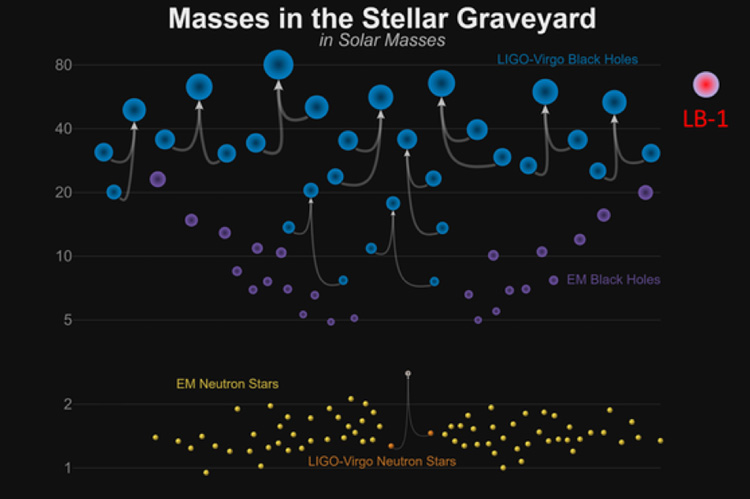

He knew black holes that size are so rare that there may be just one in the entire Milky Way Galaxy. Theoretically, black holes formed by stellar collapse in the Milky Way should weigh less than about 30 solar masses; hence the Washington Post headline reporting a “‘monster’ black hole so big they didn’t think it was possible.”

“I was suspicious from the beginning,” El-Badry says. “We know of 20 to 30 black holes in binaries, and they are all half as massive, or less than 70 solar masses. It just made me want to read the paper carefully and try to understand what (the researchers) did.”

The suspicion came from his four years of work with Eliot Quataert, a Berkeley professor and chair of the astronomy department, to discover and understand the 10 million to 100 million star-sized black holes suspected of lurking unseen in the Milky Way. These black holes are distinct from the supermassive black hole at the center of the galaxy that weighs about 4 million times more than our sun.

“We only know of a few dozen star-sized black holes in the galaxy,” Quataert says. “We need to discover more in order to understand which stars explode to become neutron stars, which ones collapse into black holes — basically, to understand the full life cycle of stars, from birth to death.”

El-Badry didn’t have time to read the new paper thoroughly until five days later, on a train back to the Bay Area after visiting his parents in Oregon. Within 15 minutes, however, he knew something about the analysis was wrong. He quickly obtained the Chinese team’s original data and, within 20 minutes, confirmed the error. On Dec. 9, a week after delving into the data, he uploaded to the internet a paper — with the admonition “not so fast” in the title — in which he described where the astronomers went wrong.

In a tweet, he wrote, “In today’s dose of cold water, we argue that the data was misinterpreted, and there is no evidence of an unusually massive BH.”

It turns out that two other research groups posted papers the same day, disputing the findings, but only El-Badry’s used the Chinese team’s original data to swat down its conclusion.

“I had reservations, too, because the long-rumored findings are not consistent with what we understand about how stars evolve,” Quataert says. “But Kareem figured out the error.”

Not so subtle error

The Chinese astronomers neglected an important complication in analyzing their data, El-Badry notes. Basically, the authors — 55 in all — ignored an aspect of the spectrum of the companion star that, if taken into account, negates their main evidence that the black hole companion was much larger than thought possible. In their paper, El-Badry and Quataert estimated that the black hole is actually between five and 20 times the mass of our sun: within the range of known stellar-mass black holes.

El-Badry admits he was excited to discover the error, yet, the discovery of a binary star system with a black hole, even if it isn’t a monster, is significant. To date, of the stellar-mass black holes discovered in our galaxy, nearly all were found because they glow brightly with X-ray emissions: The black hole is stripping matter from its stellar companion and sucking in the hot, swirling gas.

But the newly discovered binary is X-ray dark, probably because the black hole is far from its companion. Only a handful of such detached black hole binaries are known, though they may make up a significant fraction of the millions of star-sized black holes in the galaxy.

“It has been fun to work on it,” he says. “We think this is still a black hole companion, in which case it is still an interesting system — there aren’t that many of these discovered. It fits in nicely with what I am working on.”

The original paper, which the Chinese authors have not retracted, was published in one of the world’s most prestigious journals, Nature, which is known for seeking out research that makes “audacious” claims, El-Badry says.

The Chinese team discovered the binary system when it noticed that the visible member of the binary, a bright blue star, had a periodic wobble that indicated a companion was tugging on it — a rather large companion. The astronomers analyzed the star system’s wavelengths of light — the stellar spectrum — and concluded that one of its very bright features was shifting a bit, presumably because it was being red-shifted or blue-shifted as the hot gas emitted by the light swirled around the black hole at high speed. The velocity they deduced from the shifting wavelength allowed them to calculate the mass of the black hole, which they dubbed LB-1.

El-Badry found that the atmosphere of the star was absorbing that same wavelength of light — the hydrogen-alpha line — which made the emission line appear to shift when, in fact, it wasn’t. He suspects the bright emission comes mostly from material surrounding the entire binary system, not from the accretion disk of the black hole.

Nevertheless, he notes, this is the way science is done: Scientists pick apart the conclusions of other scientists to arrive at the truth. Generally, though, the fall from grace is not so rapid.