Berkeley public health projects part of UC initiative to address critical state issues

The ivory tower and the sheet-metal silo: Both of these lofty edifices have become euphemisms for the isolation in which academics often pursue their research.

The ivory tower and the sheet-metal silo: Both of these lofty edifices have become euphemisms for the isolation in which academics often pursue their research.

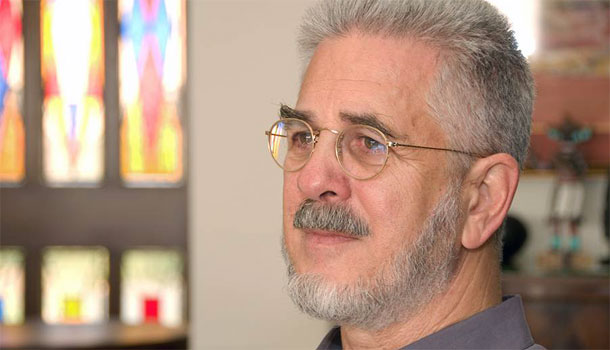

Most university systems are set up to reward such focus, and the focus in turn rewards the world with new discoveries. But philosopher Ron Glass thinks universities need a new, more open architecture if they are to help solve California’s cascading crises. He’d like to see more bridges between towers, more stairs down to the corn field. And he hopes his fledgling multicampus research center will be the catalyst.

“To ask people to work across department lines, to give up their expertise and their certainties, in order to approach things in a really radically deep and new way is not easy,” says Glass, a UC Santa Cruz professor and the director of the Center for Collaborative Research for an Equitable California (CCREC). The center is one of three dozen UC-funded Multi-Campus Research Programs and Initiatives focusing on critical issues in the state.

“Most of the institutions that now serve this state are essentially 19th century institutions, whether it’s schools or hospitals or universities or the government itself,” he says. “We need to be thinking completely outside these old boxes. Continuing to try to fix the problem with Band-Aids or emergency surgery isn’t going to work.”

There isn’t a Band-Aid to be found in CCREC’s medicine chest. The new center’s proposed tools include workshops, trainings, media, data, spaces and contexts in which people can feel comfortable outside their territory. The center draws together scholars, activists and innovators, and now has 25 fellows throughout the UC system undertaking “community-engaged” scholarship or cross-campus research. Glass aims to get at the “intersections” of issues, he says. Some of the seed projects recently funded by the center, for example, overlap research on drinking water quality and land use in the impoverished San Joaquin Valley with outreach to Mexican youth groups, struggling rural towns and local community leaders.

“Solutions to crises can’t just be recreating the status quo, because the status quo already does severe damage to populations across the state. That’s why solutions need to be equity oriented,” says Glass.

Despite criticisms that America is infatuated with self-interest, Glass believes there is still a sizable public concerned with the common good. “I’m trying to mobilize and organize those forces already in motion about equity, so they can be more effective, so their arguments can be grounded in more sophisticated social research, so solutions can be more transformative.”

Focus on forgotten people

Some of the poorest populations in California live and work in the rural reaches of the San Joaquin Valley. Nobody knows how many people really reside in the small town of South Dos Palos, for example, but last spring 30 students from UC Merced went door-to-door to find out. Such face-to-face research is sometimes the only way to document what life is like in unincorporated towns with little or no political representation, according to anthropologist and CCREC fellow Robin DeLugan. “Everyplace has a history to be told, even these forgotten places. The whole idea of our work is to help them tell their story,” she says.

DeLugan’s efforts to give a voice to people in places like South Dos Palos and Fairmead — two out-of-the-way towns whose populations have included both post-Dust Bowl African-American farmers and today’s Latino migrant workers — is part of what earned her a CCREC grant. Over the past five years, this UC Merced professor has built up trusting relationships with others concerned about the empty storefronts, lost jobs, bad water and lack of basic services in such places. The grant will enable her to collaborate with these community partners and several colleagues at UC Davis and UC Berkeley to open a “participatory action research resource center” in Fresno.

“'Let’s work together on a research project’ sounds great theoretically, but it doesn’t mean the community knows what research is, or why or how it can serve them. Nor does it mean faculty know what collaboration means, or are attentive to the power dynamics inherent when you study communities,” says DeLugan. “Communities more often feel like subjects, than partners, in research projects. They’re tired of being surveyed and never seeing the results or benefits of the surveys.” Indeed, CCREC is already crafting a new code of ethics for equity-oriented research.

Looking at low-wage workers

Reaching out to involve communities in research relevant to their lives may not be the norm, but it is nothing new. There is a whole tradition of models for how to do it. But recently, venerated public health professor Meredith Minkler worked on one of the “best projects I’ve ever been involved in, in terms of the seriousness with which it took principles of participatory engagement.”

In this project, UC Berkeley and UC San Francisco researchers teamed with San Francisco’s health department and a local labor group to look at conditions for waiters, dishwashers, cooks and other restaurant workers in Chinatown. Restaurants are the single biggest employer of Chinese migrants in the U.S.

Researchers began by hiring and training eight local low-wage restaurant workers to conduct surveys, some of whom could only speak a few words of English themselves. These trainees in turn helped design the survey, and craft questions based on their personal experience. Survey results recorded delayed pay for starting employees, employers pocketing tips, and chefs opting for short sleeves, among other problems. The short sleeves puzzled UC and health department researchers for a while, as covering up arms can prevent injuries, but they just assumed it was because kitchens were so hot. But their trainees explained that Chinese male cooks consider burns and scars badges of distinction. “If you were planning an educational intervention in this case, it would fail if you didn’t understand this cultural reality,” says Minkler, a CCREC fellow.

Eventually, this research spawned a new low-wage worker bill of rights in San Francisco. Minkler and UC colleagues stood up in front of City Hall for the rally in spring 2011. “When you’re doing this kind of work with community partners, you commit for the long haul,” she says. “We agreed we would remain active, show up at hearings, do whatever it takes to be helpful.”

Her newest project, funded with a CCREC seed grant, will use the same model to assess health impacts, if any, from the proliferation of green cleaning products on housekeepers, janitors, hotel maids and hospital staff. Everyone assumes these products are safer than conventional cleaners, but there’s no data to back that up, says Minkler.

The new project will hire and train those in the cleaning trades to survey co-workers about health and ergonomic effects: To date, the one main complaint seems to be the extra scrubbing necessary when using “natural” detergents, soaps and polishes. Professors and trainees also will be delving together into green chemistry — “co-learning,” as Minkler calls it, from both experts and users.

While these small seed projects have been sprouting around the state, CCREC has been tending to home base — setting up a governing council, looking for money, exploring partnerships with powerful businesses such as IBM. An RFP for a second round of seed projects is in the offing.

Meanwhile, Glass is pounding the pavement, talking about truth, ethics, equity and long-term thinking. “We’re in the midst of a crisis in truth,” says Glass. “Universities have always been committed to truth, but in a neutral way. I think the university now has a public service responsibility to become a gateway to reliable, equity-oriented information about issues of public concern. That’s what CCREC is trying to do, create new public learning processes.”