Berkeley links up with Facebook, but wants to see tech giant’s accountability

Facebook, weathering an onslaught of bad press, is concerned enough to have announced this week it is making a $7.5 million investment in a partnership with three universities — UC Berkeley, Cornell and Maryland — to develop new methods to improve detection of fake content, fake news and misinformation campaigns.

Hany Farid will be one of two Berkeley faculty members involved, the other being Alexei Efros of the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences (EECS), who specializes in artificial intelligence, graphics and computer vision.

Farid, who joins the faculty on a dual assignment this summer in EECS and in the School of Information, is a long-time crusader for holding social media companies accountable for removing and preventing harmful content.

“I have been skeptical,” Farid says of the new partnership. “But I have agreed to work with them for a year on the technology. For over a decade now, I’ve been pushing them and other big tech companies to take more responsibility for social media, for misinformation and fake news. I’d like to see a healthier online experience, and I am hoping that this is a first step in that direction.”

What Farid and Efros are being asked to do is to help craft that healthier experience.

“We will be working towards developing new technology to detect fake news, fake images, and fake videos,” Farid says. “This is part of a larger effort by Facebook to reign in harmful and dangerous mis-information campaigns on their platform.”

Chris Hughes, who helped found Facebook with his Harvard University roommate Mark Zuckerberg a decade and a half ago, recently wrote an op-ed in The New York Times calling for the breakup of the company. Hughes, whose net worth is $500 million, but who currently owns no Facebook stock, is disturbed by the use of Facebook by Russian operatives to interfere in the 2016 U.S. elections, the promulgation of fake news, the violent and hate-filled rhetoric seen on the site and the privacy practices that allowed tens of millions of Facebook users’ personal data to be mined.

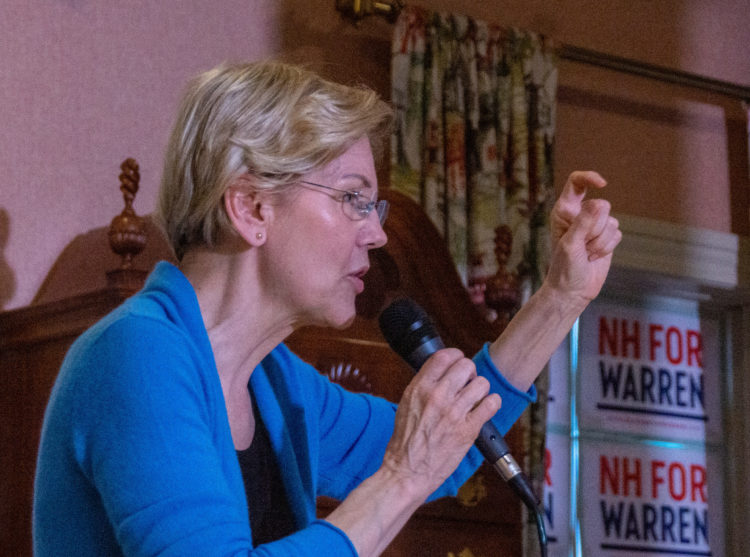

He’s not the first to suggest such a move. Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Elizabeth Warren supports a breakup of Facebook, and at least two of her opponents, Kamala Harris and Joe Biden, have said the proposal merits deeper exploration.

The primary suggestion is that Facebook be forced to sell some of its parts, including Instagram, Messenger and WhatsApp.

Farid says a breakup is one way to deal with Facebook. But he says it’s not necessarily the best solution to attack the way Facebook is exploited by those interested in promoting bullying, hate speech, loss of privacy and fake news.

He would have Facebook make a three-pronged stab. He would have the company hire more people to monitor the site, redefine Facebook and other tech giants as publishers, rather than as platforms, and charge a nominal fee to use the service.

“What matters most, if you are going to govern speech on the site, is to have clear, unambiguous rules,” Farid says. “There needs to be transparency and consistency in how the rules are enforced. The problem now is that the rules are vague, inconsistent and not consistently enforced.”

One reason for this is that Facebook uses cost-effective automation to monitor the information posted on its pages.

“In order to be able to operate at the scale of more than two billion users, they have had to fully automate most day-to-day operations,” Farid says. “There is very little human intervention. When that happens, you have problems, like people being able to advertise to ‘Jew haters’ or to advertise jobs and housing to ‘whites only.’ With more human oversight, these problems would occur with considerably less frequency. In my opinion, the primary issue is one of profits — hiring people is expensive. This type of greed is morally reprehensible, given the measurable harm that we are seeing on social media.”

Farid says he doesn’t believe that all hate speech or bullying would be eliminated by hiring humans. But “putting bodies in place to enforce the rules” would be a good first step, he says.

Farid adds that Facebook and other high-tech behemoths are hiding behind Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996. That law, written two years before the first Google search and a decade before the first Facebook post, says that, “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.”

Farid says that wording provides blanket protection against a host of laws that might hold Facebook and others legally responsible for what others say and do.

“The big tech companies say that, under the Communications Decency Act, they are just a platform for information,” Farid says. “That’s Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, all of them. But on YouTube, for example, more than half of all content is promoted by YouTube. At that point, you aren’t a platform, you are a publisher.

“If you are a publisher, you are responsible for what is said on your service. By pretending they are platforms, the big tech companies are effectively sticking their heads in the sand and ignoring the horrific things happening on their services.”

He says, “Maybe it’s time to rethink Section 230.”

Beyond that, Farid would change the Facebook business model. Instead of having all the income come from advertising, he’d have Facebook charge its patrons a nominal fee. But even a token would add up to big bucks when one-third of the global population is involved. And it would serve to make it easier for the company to monitor the site.

“The number two problem is the underlying business model,” he says. “(Facebook’s) service is free, and so they have to find a way monetize. They do that through advertising and exploiting our personal data. The free model also means that the service is largely anonymous, allowing the likes of Russian botnets to infiltrate our news feeds.”

“If you charge even $1.99 a year and enforce two-way authentication, then you have credit card information and a unique phone number linked to the user. You’d know who is there. If the user pays a fee that will sustain the companies, then they won’t need to collect our private data, or at least not as much of it. And I believe that many of the criminal issues would go away, because the criminals would have to identify themselves.

“Is there the stomach for it? I don’t know. But we are exhausted by the failures of social media. I have had people tell me they hate Facebook, they hate Twitter, they hate YouTube. But they don’t stop. They’re addicted.”