Is the Bay Area Prepared for Major Wildfires?

A UC Berkeley-led team is using computer simulations to stress-test the region’s disaster preparedness and creating virtual games to educate the public about wildfire safety.

As wildfires continue to rage in LA, many San Francisco Bay Area residents are asking themselves if a similar disaster could happen here — and, with haunting photos of abandoned vehicles in the Pacific Palisades still fresh in everyone’s minds, if vulnerable communities are prepared for a rapid evacuation and firefight.

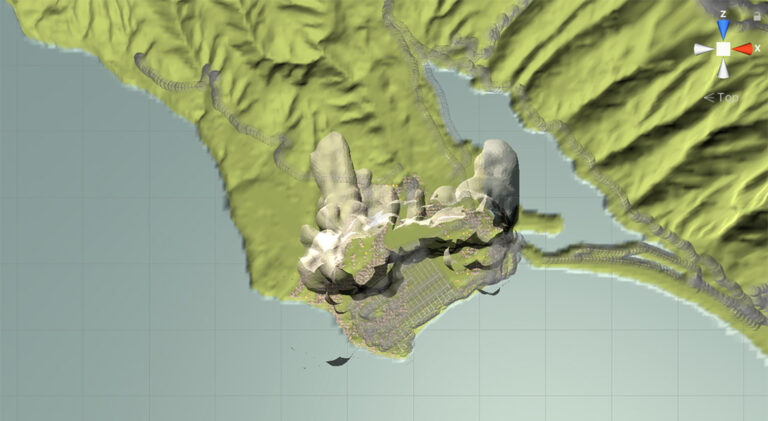

Since 2022, a team of UC Berkeley researchers, in collaboration with scientists at UC Davis and UC Santa Cruz, has been creating highly detailed models of emergency response infrastructure in two Bay Area communities to answer questions like those. These “digital twins” of Marin and Alameda counties will include communication networks, emergency services and physical infrastructure, as well as information about how different services are operated and managed. The goal of the project is to use these models to simulate wildfire evacuations under different scenarios and identify potential weaknesses.

As part of a Smart and Connected Communities project, funded by the National Science Foundation, the team is also developing virtual games that will help educate the public about wildfire readiness. The project is led by Kenichi Soga, the Donald H. McLaughlin Chair in Mineral Engineering and Chancellor’s Professor at Berkeley, and includes faculty collaborators from the Berkeley’s College of Engineering, College of Environmental Design and Rausser College of Natural Resources.

To learn more about wildfire risk in the Bay Area and how simulations and “mini-games” can help the region prepare, UC Berkeley News spoke with Louise Comfort, project co-principal investigator, professor emerita and project scientist with the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering.

UC Berkeley News: Are Bay Area communities at risk of experiencing wildfires as destructive as those currently impacting LA?

Louise Comfort: Absolutely. The Bay Area has a record of experiencing wildfire in the wildland urban interface, or areas where human development intermingles with undeveloped wildland or vegetation, approximately every 20 to 30 years. Bay Area communities have made major investments in training, preparedness and public education since the last major conflagration in 1991, but we have minor fires, such as the Keller Fire in Oakland on Oct. 20. 2024, relatively frequently. Fortunately, a well-trained Oakland Fire Department responded quickly to contain the Keller Fire, but wind-driven wildfire is a continuing threat to the region.

Compared to LA, does the Bay Area have any particular strengths or weaknesses when it comes to wildfire preparedness, in terms of susceptibility to severe fire, evacuation routes and communication, insurance coverage, etc.?

One strength is the emerging consensus among Bay Area cities that they need to collaborate to reduce wildfire risk, and further, that they need to engage residents in this shared task. There is a new regional agreement, formed just in March 2024, among a set of Bay Area jurisdictions to collaborate on wildfire risk reduction. It is called the East Bay Wildfire Coalition of Governments, with nine member jurisdictions and growing. This is an important step for local governments to pool knowledge, information, resources and plans to prepare for wildfires and other natural hazards to which all jurisdictions are exposed.

Bay Area cities are made vulnerable by structural limitations of their transportation network: four bridges, a BART train that runs part way around the Bay, limited roadways among the counties, and specific points of likely congestion. For example, if the Caldecott Tunnel is closed between Alameda and Contra Costa counties, or if the Richmond Bridge is blocked to the North Bay region, evacuation is quickly limited. Evacuation routes are problematic and dependent on other infrastructure systems, electrical power, communications and gasoline distribution — all of which are vulnerable to wind-driven wildfire.

The Smart and Connected Communities project is creating “digital twins” of two Bay Area cities to understand how they’d perform when evacuating during a natural disaster. What is a digital twin, and how will it help you understand the Bay Area’s preparedness for severe wildfire events?

A “digital twin” is a computational model of an existing urban community. It is intended to replicate technical systems of infrastructure, including road networks, water distribution systems and electrical and gasoline distribution systems. It also models how things flow through these different networks: how vehicles travel the road network, how water flows through the network of water pipes, and how electrical power and gasoline travel through their respective distribution systems. We are currently integrating these technical systems with the organizational systems that manage these functions.

The intent is to test out scenarios computationally that are too dangerous or costly to test in real time. We hope to identify the strengths and weaknesses of our present organizational, institutional and technical infrastructures before an extreme event — wildfire, earthquake, tsunami, atmospheric river rainstorm or flooding — occurs, so we can anticipate possible scenarios for mitigating these risks or respond quickly to reduce the impact when they do.

How do you hope to engage communities to build awareness of risks of preparation?

We have done a series of semi-structured interviews with community leaders, public managers and administrators in public organizations, like schools, parks and hospitals to identify networks of communication and collaboration within communities, as well as gaps in social interaction that limit full community response. We are working with a talented team of computer scientists at UC Santa Cruz who have developed a series of “mini-games,” or simulated games that illustrate common dilemmas that people face when encountering a wildfire situation. Such simulations enable people to think through dilemmas before the wildfire occurs, identify alternatives for action in a specific context, and connect with neighbors in a shared task of enabling everyone to evacuate safely.

We hope to hold a public community meeting in late spring 2025 and invite people to come and play the games and give us feedback. We also will make the mini-games available for use in small groups, such as Fire Safe Councils, so members of a neighborhood group can play the game together and think about strategies of risk reduction for their neighborhoods.

Could this model be applied to other disasters that threaten the Bay Area, like sea level rise, flooding or earthquakes?

Absolutely. The task is the same for any hazard — wildfire, earthquakes, flash floods, landslides — even if the specific actions may differ by hazard. It means recognizing the risk in a specific context, then determining what resources are available to an individual, household, neighborhood, municipality or county to reduce that risk. It means understanding the risk in one’s specific neighborhood and determining what options are available to manage that risk. These are practical steps that greatly increase a community’s capacity for collective action under threat.