After a blitz of police killings, reformers focus on the power of their unions

Pressure for police reform is mounting after the guilty verdicts against former Minneapolis officer Derek Chauvin and a new burst of police killings, and reformers nationwide are increasingly focused on a key component of law enforcement culture: police unions.

Across the nation, unions and their leaders have strongly defended officers against accusations of excessive violence, often directed against people of color. Cities are dangerous places, they say, and that justifies a warrior-like approach to policing.

But in a series of interviews, Berkeley scholars said police unions have successfully used a range of tools, from the fine print in labor contracts to millions of dollars in political donations, to shield officers from accountability and promote hardline policing practices. While discipline is often secret and officers rarely lose their jobs, they say, cities have paid tens of millions of dollars in settlements with recent victims.

In New York City, a powerful union leader threatened a work slowdown after a white officer was fired for killing Eric Garner, a Black man. In Chicago, a union leader expressed support for the Jan. 6 attack at the U.S Capitol. And in Missouri, one major union embraced legislation to allow the use of deadly force against protesters on private property and give legal immunity to drivers who hit demonstrators blocking traffic.

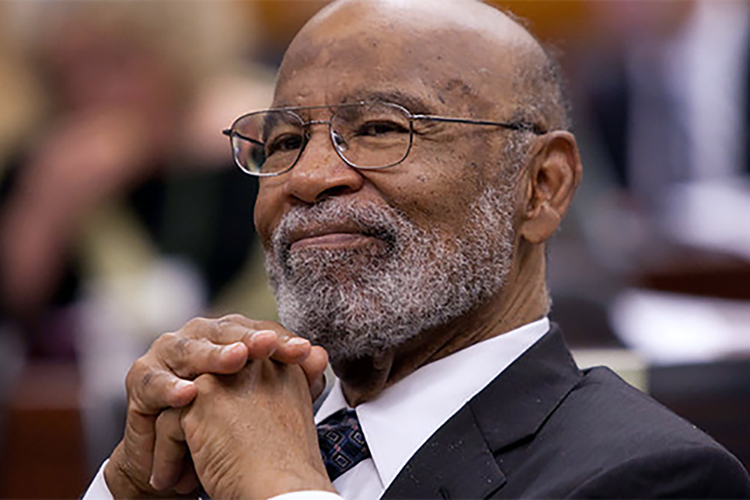

“I think the unions are a big problem,” said retired U.S. District Court Judge Thelton Henderson, who spent the last part of his career overseeing reforms at the Oakland Police Department. “They feel their strength comes from protecting their members, and so they do everything to protect the members no matter what they do.… In their view, there’s no such thing as a bad apple that they have to pull out of the barrel.”

Henderson is now a visiting scholar at the UC Berkeley School of Law, and he recently worked with law Professor Catherine Fisk and other top legal experts on a framework for reform in California law that would increase transparency and public oversight of police labor negotiations and disciplinary processes.

If unions are “not effectively challenged by management, by elected officials, by numerical and perhaps racial minorities within police departments for fear of retaliation,” Fisk said in an interview, then the unions’ muscular exercise of power “feeds on itself and becomes ever more extreme.”

Targeting secrecy, increasing transparency

Police unions are not alone to blame for bad practices or individual misconduct, the Berkeley experts said. Police leaders share the blame, because they often sidestep the hard work of discipline and reform. Elected officials are to blame, too, because they sometimes accept union support and then go soft on oversight. And the public is to blame, they say, because in the zeal to stop crime, voters have tolerated a range of abuses.

But Fisk and others have argued that reforming police unions would put a check on police power and make them more accountable to the public.

In a 2017 research paper, Fisk and UC Irvine law Dean L. Song Richardson argued that other unions — for example, associations of Black or women police officers — should have greater power to engage with police leaders on matters of department policies and practices. That could allow more influence for officers who disagree with positions taken by the dominant union, she said.

Last year, Fisk and Henderson teamed with former California Supreme Court Justice Joseph Grodin and other legal experts to offer a broad plan that would make police unions more accountable to elected officials and the public. They proposed changes to California law that would:

- Increase transparency: The public would have greater access to contract negotiations, negotiations over policy that governs police use of force, and records on complaints and discipline against officers.

- Make it easier to tighten use-of-force rules: Top police officials would be permitted to override police labor contracts to reform the policies on when cops can use force.

- Reform disciplinary proceedings: Arbitrators would be able to consider past complaints and disciplinary action against an officer. In decisions to reinstate officers fired for misconduct, the arbitrators would be required to consider not just the officer’s interest, but the public’s interest. Disciplinary proceedings would be opened to the public.

Fisk noted that police officers are public workers just like teachers. “What a government employee does in the name of the public — if I am harming students in my classroom, I have no privacy right,” she said. “Nor should a cop.”

How the power of police unions warps police practices

Unions amassed vast and often unchallenged power starting in the 1960s. After years of civil unrest, the political climate shifted dramatically: The public was obsessed with crime and security, and that gave police enormous credibility with voters — and it gave police unions enormous leverage with elected officials.

“Like any effective interest group, they raise and contribute large sums of money to candidate campaigns,” said veteran strategist Dan Schnur, a Berkeley political science lecturer. “They also develop great influence by lending their reputation and credibility to politicians who ally themselves with the unions.

“The check and the badge make for a pretty powerful one-two impact.”

A large crowd gathered in Minneapolis in 2016 to protest the police killing of 24-year-old Jamar Clark several months earlier. The Minneapolis Police Department has frequently come under scrutiny for officer killings of people of color, and some critics have charged that the police union and its leaders have played a central role in shaping a culture of violence and racism. (Wikipedia Commons photo by Fibonacci Blue)

In recent years, from New York and New Orleans to Chicago, Albuquerque and Los Angeles — and even in the small city of Vallejo, Calif. — police unions have been criticized for defending officers accused of violence and for blocking reform.

In Minneapolis, the police department had been criticized for patterns of excessive violence and racial discrimination long before Chauvin was found guilty last week of murder and manslaughter for killing George Floyd 11 months ago.

But many critics say the city’s police union and its elected president, Lt. Bob Kroll, have been powerful forces shaping police culture and blocking reform. In a career spanning more than 30 years, Kroll was involved in three shootings and attracted some 20 complaints for wrongful arrest and excessive force. He was sued, disciplined and demoted for misconduct.

After Chauvin killed Floyd, Kroll described the victim as a “violent criminal.” He called Black Lives Matter a “terrorist organization.”

In Oakland, Calif., a corruption case that emerged in 2000 accused four rogue officers — known as the “Riders” — of planting evidence, brutality and racial discrimination, much focused on people in low-income neighborhoods. Under a 2003 settlement overseen by Henderson, the federal district court judge, the Oakland Police Department was to implement dozens reforms to prevent future corruption and violence.

Nearly 18 years later, Henderson has retired and police chiefs have come and gone, but the department still has not achieved all of the reforms, and incidents of police violence and racial profiling persist. In the keynote address to a Berkeley Law webinar in January, Henderson placed responsibility on the police union.

“We know something is wrong,” Henderson said, “when a city and police department enter into a negotiated settlement agreement and over the course of 20 years — and with near impunity — (the union) refuses to do that to which it has agreed, and at a cost of millions and millions of taxpayer dollars.”

Police unions and police racism: a costly link

At the Berkeley Law webinar, top U.S. policing experts offered a blunt assessment: Racism plagues some police departments and police unions, and that leads to policing problems.

Ronald L. Davis, a Black former Oakland police officer and chief of the East Palo Alto Police Department, served from 2013 to 2017 as director of the Office of Community Oriented Policing Services at the U.S. Department of Justice. At the Berkeley Law panel, he expressed frustration that many police embrace the Blue Lives Matter movement.

“The refusal to accept that there’s still structural racism, and to deny that by then creating Blue Lives Matter, as if we’re all on equal planes — that is a problem that contributes to a culture that then protects misconduct and encourages certain ideological views that are counterproductive to police reform,” Davis said.

Christy E. Lopez, a Georgetown University law professor and former top Justice Department official, conducted federal investigations of many troubled police departments. “Explicit racism and the use of egregious force with absolute impunity has been normalized within the ranks, not just of policing, but within the leadership of their recognized representatives,” Lopez told the Berkeley audience. “We should be horrified.”

Such misconduct erodes a community’s trust of police, but it also carries enormous financial costs:

$10.9 million in Oakland, $1.5 million in Ferguson, Missouri, $33 million in Chicago, and most recently $27 million in Minneapolis, a settlement paid by the city to George Floyd’s family.

People in these cities “might feel themselves victimized twice,” Fisk said, “once by police who abuse them, and then again when they’re paying for the police abuse.”

In the aftermath of Chauvin, an opening for reform?

Even as the Chauvin case was unfolding this month, police have been criticized for shootings of Black people in Chicago; Columbus, Ohio; Elizabeth City, North Carolina; and Brooklyn Center, Minnesota. Now the culture advanced for 50 years by American police unions appears to be facing a backlash — and experts see signs of a possible opening to reform.

Kroll, in January, unexpectedly announced his retirement. In Brooklyn Center, the officer who fatally shot Daunte Wright was quickly arrested and charged with second-degree manslaughter.

Earlier this month, the Maryland state legislature pushed through a historic reform of policing, taking away many of the protections previously won by police unions.

And the Justice Department has opened investigations into police departments in Minneapolis and Louisville, Kentucky, where Breonna Taylor was killed last year.

Fisk says reform will be most effective if police are part of the process. In fact, Berkeley experts say, a generational change may be underway in policing, and an increasingly diverse cadre of younger officers may be supportive of reform. In time, that may force unions to change, too.

Schnur, the UC Berkeley political science lecturer, says that after decades of dramatic gains, police unions are now in a defensive crouch, using donations and lobbying not to advance their power, but to preserve it. But, he said, they face a political climate that is increasingly impatient.

“The most productive unions, whether in law enforcement or in any other field, are those that work with the public rather than against the public,” Schnur said. “You can say the same thing about teachers unions, about public employees unions. But because the stakes relating to public safety are so high, the debate about police unions becomes much more charged.”