Research Bio

Rasmus Nielsen is an evolutionary biologist and geneticist whose research investigates human evolution, population genetics, and statistical genomics. He is best known for developing computational methods to detect natural selection in genomes and for his discoveries on human adaptation to high-altitude environments and ancient interbreeding with Neanderthals and Denisovans. Nielsen’s research integrates evolutionary theory, bioinformatics, and molecular biology to uncover the genetic basis of adaptation and diversity across species. His work has transformed our understanding of human evolution and evolutionary genomics.

He is Professor of Integrative Biology and Statistics at UC Berkeley and a member of the Center for Theoretical Evolutionary Genomics. He has published more than 350 peer reviewed publications including many in Nature, Science, and Cell. Nielsen is a member of the National Academy of Sciences and the Danish Royal Academy of Sciences. At Berkeley, he teaches Human Biological Variation and mentors students in computational biology and evolutionary research.

Research Expertise and Interest

evolution, molecular evolution, population genetics, human variation, human genetics, phylogenetics, applied statistics, genetics, evolutionary processes, evolutionary biology

In the News

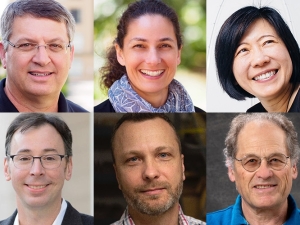

Six Berkeley Faculty Members Elected to National Academy of Sciences

Tales from 141,430 and one genomes

Enlarged spleen key to diving endurance of ‘sea nomads’

What the Inuit can tell us about omega-3 fats and ‘paleo’ diets

The traditional diet of Greenland natives – the Inuit – is held up as an example of how high levels of omega-3 fatty acids can counterbalance the bad health effects of a high-fat diet, but a new study hints that what’s true for the Inuit may not be true for everyone else.

Genome Analysis Pinpoints Arrival and Spread of First Americans

The original Americans came from Siberia in a single wave no more than 23,000 years ago, at the height of the last Ice Age, and apparently hung out in the north – perhaps for thousands of years – before spreading in two distinct populations throughout North and South America, according to a new genomic analysis.

Extinct human cousin gave Tibetans advantage at high elevation

Tens of thousands of years ago, the common ancestors of Han Chinese and Tibetans interbred with a mysterious human-like group known as Denisovans and picked up a unique variant of a gene for hemoglobin regulation that later helped them adapt to a low-oxygen environment on the high Tibetan plateau, reports UC Berkeley professor of integrative biology Rasmus Nielsen

Polar bear genome gives new insight into adaptations to high-fat diet

A comparison of the genomes of polar bears and brown bears reveals that the polar bear is a much younger species than previously believed. Also uncovered were several genes that may be involved in the polar bears’ extreme adaptations to life in the high Arctic.

Study dispels theories of Y chromosome’s demise

A comparison of Y chromosomes in eight African and eight European men dispels the common notion that the Y‘s genes are mostly unimportant and that the chromosome is destined to dwindle and disappear.

Scientists look to Hawaii’s bugs for clues to origins of biodiversity

The Hawaiian Islands are a unique and ongoing series of evolutionary and ecological experiments. As each volcano rises above the waves, it is colonized by life from neighboring volcanoes and develops its own flora and fauna.

Tibetans adapted to high altitude in less than 3,000 years

UC Berkeley's Rasmus Nielsen teamed up with Chinese researchers to compare the genomes of Tibetans living above 14,000 feet to Han Chinese living at essentially sea level. They found that within the last 3,000 years, Tibetans evolved genetic mutations in a number of genes having to do with how the body deals with oxygen, making it possible for Tibetans to thrive at high altitudes while their Han relatives cannot.