Research Bio

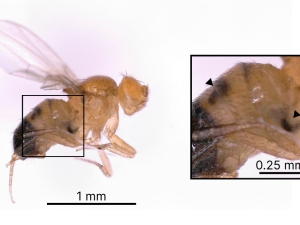

Noah Whiteman is an evolutionary biologist and geneticist who studies the molecular basis of co-evolution between species. Co-evolution occurs when one species like a host, adapts to another, like a parasite, and vice versa, which is hypothesized to have helped generate the great diversity of life on Earth. Whiteman and his laboratory members have pioneered the use of molecular genetics to understand the process of co-evolution and the development of new models to study the molecular mechanisms that drive it, from host-parasite systems in the Galápagos Islands to those along Strawberry Creek on the Berkeley campus. His laboratory uses genome editing technology, including CRISPR-Cas9, to "replay the tape" of evolution and reconstruct the paths that co-evolution has taken, including how monarch butterflies evolved to resist the high levels of cardiac glycoside heart poisons in their bodies that they obtain from milkweed host plants. Monarchs famously use these defenses against predators like birds during their extraordinary yearly migration from the prairies of Canada to the mountains of Mexico. Most recently, his laboratory has focused on understanding how Drosophila "vinegar" flies have borrowed genes from bacteria and viruses that encode toxic enzymes against their main animal enemies, the parasitoid wasps (which inspired the Xenomorphs from the movie Alien). He and his laboratory are using this fly-parasitoid wasp system as a model for understanding how both hosts and parasites tap into the armamentarium of microbes, in both defense and offense. The toxic molecules that Whiteman studies are often used as medicines as part of the human pharmacopeia, as he recently wrote about for Asimov Press. Whiteman works to communicate the scientific discoveries made by his laboratory with the public and is the author of the book Most Delicious Poison, which brings Darwin's "war of nature" to a broad audience.

At Berkeley, Whiteman is Professor of Genetics, Genomics, Evolution and Development in the Department of Molecular & Cell Biology (100%) and Department of Integrative Biology (0%). He is also the lead co-Director of the Genetic Dissection of Cells and Organisms Training Program (GDTP) with co-Director and Professor Nicole King. The GDTP is a pre-doctoral T32 program funded by the NIH and trains 16 Ph.D. students in advanced genetics across the life sciences at Berkeley.

Whiteman is the recipient of the 2025 Genetics Society of America Medal for "outstanding contributions to the field of genetics" and a 2020 Guggenheim Fellowship in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.

Research Expertise and Interest

adaptation, evolutionary biology, genomics, genetics, toxicology, insect biology, plant biology, microbiology, CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing

In the News

Watch a Professor Explain the Evolutionary War That Gave Us Caffeine

Fly vs. Wasp: Stealing a Defense Move Helps Thwart a Predator

Nature’s Poisons: Why We Love Them and Abuse Them

What It Takes to Eat a Poisonous Butterfly

CRISPRed flies mimic monarch butterfly — and could make you vomit

Featured in the Media

Noah Whiteman, Professor of Genetics, Genomics, Evolution and Development, is a 2025 recipient of the Genetics Society of America Medal for outstanding contributions to the field of genetics.

"Many baroque chemicals we use and abuse appeared on the planet because they enhance the survival odds of the organisms that make them or absorb them through their diet or microbiome," writes Noah Whiteman, integrative biology professor.