Research Bio

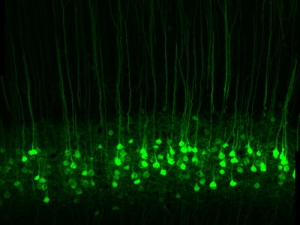

Dan Feldman is a neuroscientist whose research focuses on sensory processing, synaptic plasticity, and neural circuit function in cerebral cortex. His work uses electrophysiology, imaging, and computational modeling to reveal how the somatosensory cortex encodes touch, the structure of neural codes in sensory cortex, and how experience modifies neural connections to shape perception and learning. Feldman's work provides insight into the mechanisms for brain plasticity, and how the brain continuously adapts to maintain proper cortical function across age and experience. He also studies the neural circuit mechanisms that drive altered sensory processing in severe genetic forms of autism.

He is Professor and Chair of the Neuroscience Department, and a member of the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute. He mentors students in cellular and systems neuroscience.

Research Expertise and Interest

neurobiology, learning, neurophysiology, sensory biology

In the News

Mouse studies question ‘inhibition’ theory of autism

NIH awards UC Berkeley $7.2 million to advance brain initiative

The National Institutes of Health today announced its first research grants through President Barack Obama’s BRAIN Initiative, including three awards to the University of California, Berkeley, totaling nearly $7.2 million over three years.