Research Bio

Burkhard Militzer is a Professor of Earth and Planetary Science. His research focuses on studying Earth and Planetary Science problems using computer simulation techniques that were developed in condensed matter physics. Recent studies focused hydrogen-helium mixtures in Jupiter and whether this planet has a rocky core. The comparison of theory and experiment is very important, but with computer simulations one can study much higher pressures than are accessible in experiments, and that is needed to understand giant planet interiors.

Research Expertise and Interest

density functional methods, equation of state calculations, planetary interiors, materials at high pressure, theoretical mineral physics, path integration Monte Carlo, planet formation, quantum Monte Carlo method

In the News

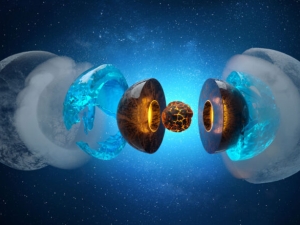

A Clue to What Lies Beneath the Bland Surfaces of Uranus and Neptune

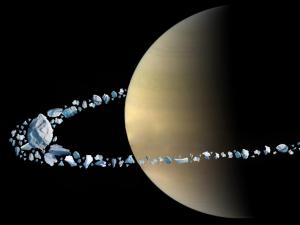

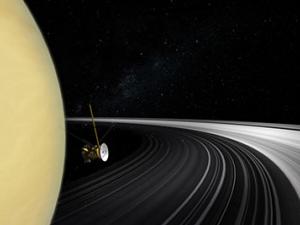

Chrysalis, the Lost Moon That Gave Saturn Its Rings

Saturn hasn’t always had rings

What magnetic fields can tell us about life on other planets

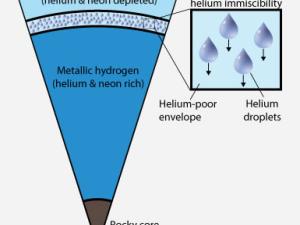

Helium rain on Jupiter explains lack of neon in atmosphere

When the Galileo probe descended through Jupiter's atmosphere in 1995, it found neon to be one-tenth as abundant as predicted. This unexpected finding has led two UC Berkeley researchers to propose that this is due to a rain of helium that depletes Jupiter's layers of neon as well as helium.

Featured in the Media

Astronomy Professor Burkhard Militzer's "idea could explain a key difference between Jupiter and Saturn, which are mostly composed of hydrogen, and Uranus and Neptune."