Jupiter-like exoplanets found in sweet spot in most planetary systems

As planets form in the swirling gas and dust around young stars, there seems to be a sweet spot where most of the large, Jupiter-like gas giants congregate, centered around the orbit where Jupiter sits today in our own solar system.

The location of this sweet spot is between 3 and 10 times the distance Earth sits from our sun (3-10 astronomical units, or AU). Jupiter is 5.2 AU from our sun.

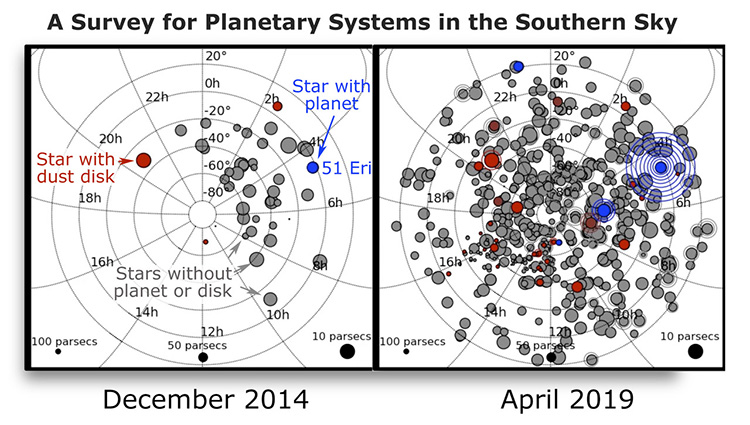

That’s just one of the conclusions of an unprecedented analysis of 300 stars captured by the Gemini Planet Imager, or GPI, a sensitive infrared detector mounted on the 8-meter Gemini South telescope in Chile.

The GPI Exoplanet Survey, or GPIES, is one of two large projects that search for exoplanets directly, by blocking stars’ light and photographing the planets themselves, instead of looking for telltale wobbles in the star — the radial velocity method — or for planets crossing in front of the star — the transit technique. The GPI camera is sensitive to the heat given off by recently-formed planets and brown dwarfs, which are more massive than gas giant planets, but still too small to ignite fusion and become stars.

The analysis of the first 300 of more than 500 stars surveyed by GPIES, published June 12 in the The Astronomical Journal, “is a milestone,” said Eugene Chiang, a UC Berkeley professor of astronomy and member of the collaboration’s theory group. “We now have excellent statistics for how frequently planets occur, their mass distribution and how far they are from their stars. It is the most comprehensive analysis I have seen in this field.”

The study complements earlier exoplanet surveys by counting planets between 10 and 100 AU, a range in which the Kepler Space Telescope transit survey and radial velocity observations are unlikely to detect planets. It was led by Eric Nielsen, a research scientist at the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology at Stanford University, and involved more than 100 researchers at 40 institutions worldwide, including the University of California, Berkeley.

One new planet, one new brown dwarf

Since the GPIES survey began five years ago, the team has imaged six planets and three brown dwarfs orbiting these 300 stars. The team estimates that about 9 percent of massive stars have gas giants between 5 and 13 Jupiter masses beyond a distance of 10 AU, and fewer than 1 percent have brown dwarfs between 10 and 100 AU.

The new data set provides important insight into how and where massive objects form within planetary systems.

“As you go out from the central star, giant planets become more frequent. Around 3 to 10 AU, the occurrence rate peaks,” Chiang said. “We know it peaks because the Kepler and radial velocity surveys find a rise in the rate, going from hot Jupiters very near the star to Jupiters at a few AU from the star. GPI has filled in the other end, going from 10 to 100 AU, and finding that the occurrence rate drops; the giant planets are more frequently found at 10 than 100. If you combine everything, there is a sweet spot for giant planet occurrence around 3 to 10 AU.”

“With future observatories, particularly the Thirty-Meter Telescope and ambitious space-based missions, we will start imaging the planets residing in the sweet spot for sun-like stars,” said team member Paul Kalas, a UC Berkeley adjunct professor of astronomy.

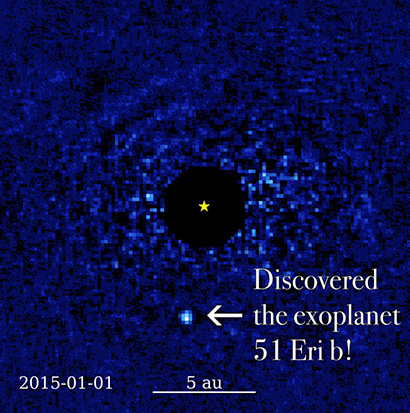

The exoplanet survey discovered only one previously unknown planet — 51 Eridani b, nearly three times the mass of Jupiter — and one previously unknown brown dwarf — HR 2562 B, weighing in at about 26 Jupiter masses. None of the giant planets imaged were around sun-like stars. Instead, giant gas planets were discovered only around more massive stars, at least 50 percent larger than our sun, or 1.5 solar masses.

“Given what we and other surveys have seen so far, our solar system doesn’t look like other solar systems,” said Bruce Macintosh, the principal investigator for GPI and a professor of physics at Stanford. “We don’t have as many planets packed in as close to the sun as they do to their stars and we now have tentative evidence that another way in which we might be rare is having these kind of Jupiter-and-up planets.”

“The fact that giant planets are more common around stars more massive than sun-like stars is an interesting puzzle,” Chiang said.

Because many stars visible in the night sky are massive young stars called A stars, this means that “the stars you can see in the night sky with your eye are more likely to have Jupiter-mass planets around them than the fainter stars that you need a telescope to see,” Kalas said. “That is kinda cool.”

The analysis also shows that gas giant planets and brown dwarfs, while seemingly on a continuum of increasing mass, may be two distinct populations that formed in different ways. The gas giants, up to about 13 times the mass of Jupiter, appear to have formed by accretion of gas and dust onto smaller objects — from the bottom up. Brown dwarfs, between 13 and 80 Jupiter masses, formed like stars, by gravitational collapse — from the top down — within the same cloud of gas and dust that gave rise to the stars.

“I think this is the clearest evidence we have that these two groups of objects, planets and brown dwarfs, form differently,” Chiang said. “They really are apples and oranges.”

Direct imaging is the future

The Gemini Planet Imager can sharply image planets around distant stars, thanks to extreme adaptive optics, which rapidly detects turbulence in the atmosphere and reduces blurring by adjusting the shape of a flexible mirror. The instrument detects the heat of bodies still glowing from their own internal energy, such as exoplanets that are large, between 2 and 13 times the mass of Jupiter, and young, less than 100 million years old, compared to our sun’s age of 4.6 billion years. Even though it blocks most of the light from the central star, the glare still limits GPI to seeing only planets and brown dwarfs far from the stars they orbit, between about 10 and 100 AU.

The team plans to analyze data on the remaining stars in the survey, hoping for greater insight into the most common types and sizes of planets and brown dwarfs.

Chiang noted that the success of GPIES shows that direct imaging will become increasingly important in the study of exoplanets, especially for understanding their formation.

“Direct imaging is the best way at getting at young planets,” he said. “When young planets are forming, their young stars are too active, too jittery, for radial velocity or transit methods to work easily. But with direct imaging, seeing is believing.”

Other UC Berkeley team members are postdoctoral fellows Ian Czekala, Gaspard Duchêne, Thomas Esposito, Megan Ansdell and Rebecca Jensen-Clem, professor of astronomy James Graham and undergraduates Jonathan Lin, Meiji Nguyen and Yilun Ma. Other team members include Nielsen, a former Berkeley undergraduate, Franck Marchis, a former assistant researcher, and Marshall Perrin, Mike Fitzgerald, Jason Wang, Eve Lee and Lea Hirsch, former graduate students.

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation (AST-1518332), National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NNX15AC89G) and the Nexus for Exoplanet System Science (NExSS), a research coordination network sponsored by NASA’s Science Mission Directorate (NNX15AD95G).

RELATED INFORMATION