Bringing Indigenous Knowledge to Neuroscience

Andrea Gomez, a 2021 Rose Hill Innovator, is probing how our brains learn and change over time by studying how the compounds found in psychedelic mushrooms influence brain activity.

The human brain has an immense power to change; over our lifetimes we grow and learn and shift our beliefs and preferences about the world. We recover from trauma and develop new skills. With each transformation, our brains forge new connections.

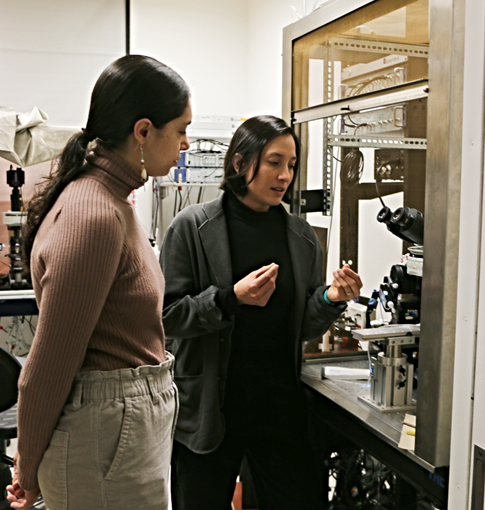

Andrea Gomez, an assistant professor of molecular and cell biology and a faculty affiliate of the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute, wants to know how cells and molecules in the brain enable that flexibility and change— called brain plasticity. To understand this brain plasticity better, she’s studying the impact of psychedelic compounds, such as those found in psychedelic mushrooms, on mice. These compounds, which include psilocybin, offers a controlled way to boost brain plasticity, she says.

“These compounds profoundly change the way people feel and behave long after any exposure to the medicine,” says Gomez. “I think that understanding how psychedelics change the brain can give us a window into how we can manipulate the brain in other ways— including how to treat neurological diseases that impact learning and memory.”

Gomez, who was awarded a 2021 Rose Hill Innovator grant for the project, not only brings a curiosity about neuroscience to her research, but also a deep appreciation for the ancient roots of psilocybin. A Chicano and Laguna Pueblo Native, she thinks ancient knowledge on the drug’s medicinal use is important to integrate into even the most basic, molecular studies.

“I’m very motivated by ensuring that this indigenous knowledge is recognized and honored and has the same respect as western medical innovations,” she says.

A longtime love of science

Despite her fascination with what allows the brain to change, Gomez has had relatively steady interests for decades. She wanted to be a scientist as far back as she can remember, she says; in second grade in Las Cruces, New Mexico, she declared that she was going to be a microbiologist.

When she was 16, Gomez had her first hands-on research experience, participating in “Medicinal Plants of the Southwest,” a summer program at New Mexico State University. She and other students learned molecular biology techniques—measuring the active components of a psychoactive plant, for instance. But they also approached the medical plants through anthropology, discussing topics like how a plant might also be able to be woven into a basket.

Gomez was hooked on research and went on to get an undergraduate degree in biology from Colorado State University, where her research focused on something very different: what genes and molecules make it possible for crabs to shed their entire exoskeletons in the molting process.

“This seems very far afield from what I do now,” says Gomez. “But it’s actually what first got me interested in some of these fundamental questions about how an organism can change so drastically over their lifetime.”

It was during graduate school at New York University that Gomez began to steer her research into the neuroscience realm, working on pinpointing molecular pathways that let the brain change. Brain plasticity, she says, walks a fine line. Too much constant change in the brain would mean we couldn’t retain memories and knowledge, while not enough change would mean we couldn’t form new connections in the first place.

Throughout her early career, Gomez also continued to embrace her background. “I didn’t know any indigenous scientists when I was training but I had a lot of support through Native American clubs and retention programs,” she says.

Launching a Lab

In 2020, Gomez moved from a post-doctoral fellowship at the University of Basel, in Switzerland, to Berkeley to launch her own lab. But COVID made it impossible to ship the mice she needed for experiments from Switzerland to the U.S. So when a colleague suggested a different avenue of work—studying the role of psilocybin in brain plasticity— Gomez jumped on board.

“The fact that I had a chance to synthesize indigenous science and western science was really exciting to me,” says Gomez, who is now also a member of the Berkeley Center for the Science of Psychedelics and recently co-founded a Berkeley scholarship for indigenous students studying science.

Today, she is focused on how psilocybin changes levels of certain RNA molecules in the brain and, as a result, turns genes on and off. If she can discover key molecules that allow psilocybin to boost brain plasticity, pharmaceutical compounds could be developed that increase plasticity in disease contexts. For instance, a drug could make it easier for patients with Alzheimer’s disease to form new memories.

“The fact that our genomes encode information that allows us to change over time is the most profound and exciting thing to me,” says Gomez. ”I think understanding these ancient systems helps fulfill my curiosity about how we came to be, where we’re going, and how much we can change.”