Research Bio

Jill Banfield is Professor in the Departments of Earth and Planetary Science and Environmental Science, Policy, and Management. She is the Director of the Innovative Genomics Institute Microbiology Program and also has an appointment in the geochemistry group at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Her primary research interests are in microbial communities, and environmental microbiology, microbial, viral and phage diversity, and evolution. Her research group studies how microorganisms shape, and are shaped by, their natural environments. Her research group primarily uses cultivation-independent approaches such as metagenomics, metatranscriptomics and community proteomics to understand how microbial consortia interact with and are shaped by their environments, with implications for climate change research, agriculture and human health.

Research Expertise and Interest

genomics, geomicrobiology, biogeochemistry, carbon cycling, minerology

In the News

Creature the Size of a Dust Grain Found Hiding in California’s Mono Lake

IGI’s ‘Audacious’ New Frontier for CRISPR: Editing Microbiomes for Climate and Health

Like the Borg of Star Trek, These ‘Aliens’ Assimilate DNA From Other Microbes

In 10 years, CRISPR Transformed Medicine. Can It Now Help Us Deal With Climate Change?

Chan Zuckerberg Initiative Puts $11 Million Into Carbon Capture Research

Jill Banfield: How a curious Google search led me to Jennifer Doudna

Huge bacteria-eating viruses narrow gap between life and non-life

Whopping big viruses prey on human gut bacteria

Soil prospecting yields wealth of potential antibiotics

CZ Biohub awards nearly $14.5 million to Berkeley researchers

CRISPR research institute expands into agriculture, microbiology

New Bacteria Groups, and Stunning Diversity, Discovered Underground

Wealth of unsuspected new microbes expands tree of life

Newfound groups of bacteria are mixing up the tree of life

Jill Banfield, professor of EPS and ESPM, and grad student Christopher Brown discovered a large number of new groups or phyla of bacteria, suggesting that the branches on the tree of life need some rearranging. The more than 35 new phyla equal in number all the plant and animal phyla combined.

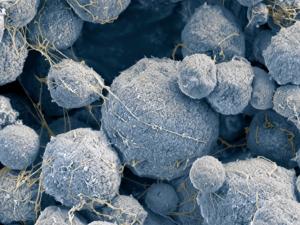

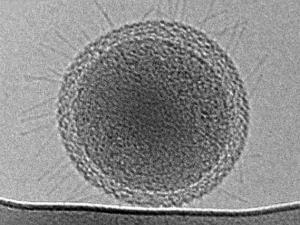

First Detailed Microscopy Evidence of Bacteria at the Lower Size Limit of Life

Scientists have captured the first detailed microscopy images of ultra-small bacteria that are believed to be about as small as life can get. The research was led by scientists from Berkeley Laboratory and UC Berkeley.

Eel River Observatory seeks clues to watershed’s future

University of California, Berkeley, scientists will receive $4,900,000 over the next five years to study the nearly 10,000 square kilometer Eel River watershed in Northern California and how its vegetation, geology and topography affect water flow all the way to the Pacific Ocean.

New Berkeley Lab Subsurface SFA 2.0 Project Explores Uncharted Environmental Frontier of Subsurface Ecogenomics

The key to a better understanding of the carbon cycle, the flow of contaminants, even the sustainable growth of biofuel crops, starts with the ground beneath your feet. More specifically, it starts with the genomes of the microbes that live in the water and sediment beneath your feet.

Contaminated site yields wealth of information on microbes 10 feet under

UC Berkeley scientists have dug into the soil of a heavy metal contaminated site to analyze the genes of the underground microbial community in hopes of finding ways to help improve the microbes’ ability to remediate toxic metal contamination.

Berkeley biogeochemist and geomicrobiologist Jillian Banfield studies very, very small things

But her work is vast in its scope and impact. So vast, in fact, that her discoveries have implications for space, the human body, and nearly everything in between.

Jillian Banfield profiled in L’Oréal-UNESCO video

UC Berkeley’s Jillian Banfield was named the 2011 North American Laureate at the 13th Annual L’Oréal-UNESCO For Women in Science Awards ceremony in Paris on March 3, which included the screening of a video interview with Banfield discussing her research and philosophy of science.

Microbes in the preemie gut

UC Berkeley scientist Jill Banfield, with colleagues at the University of Pittsburgh and Stanford University, have for the first time sequenced and reconstructed the genomes of most of the microbes in the gut of a premature newborn and documented how the microbe populations changed over time. Banfield and pediatric surgeon Michael Morowitz hope that characterizing gut microbes of normal and sick infants could lead to cause of necrotizing enterocolitis in preemies.

Jillian Banfield to receive Franklin Medal, L'Oreal-UNESCO award

Jillian Banfield, a biogeochemist and geomicrobiologist, will receive two prestigious awards – the Benjamin Franklin Medal in Earth and Environmental Science and the L-Oréal-UNESCO "For Women in Science" award – for her groundbreaking work on how microbes alter rocks and interact with the natural world.

Weird, ultra-small microbes turn up in acidic mine drainage

For nearly a decade, Jillian Banfield and her UC Berkeley colleagues have been studying the microbe community that lives in one of the most acidic environments on Earth: the drainage from a former copper mine in Northern California. One group of these microbes seems to be smaller, and weirder, than any other known, free-living organism.