Small Salmon, Big Threat

When you think of salmon bucking the rapids with a single, urgent purpose, the image of a barely trickling stream probably doesn’t come to mind. But in Central California – the southern end of salmon’s range – many streams that feed roiling rivers in winter shrink to isolated pools by summer’s end.

Steelhead trout and coho salmon breed in these streams and juveniles hatch in early spring, remaining for one to two years before heading out to sea. These two–to four–inch juveniles face their toughest survival test when late summer water levels drop and water temperatures rise during California’s long, dry season.

The fish are native to some of the region’s thousands of miles of intermittent streams, and they have adapted to dry spells, often congregating in shaded pools where larger, salmon-eating fish can’t survive. But water demands for agriculture and a changing climate will likely shrink these pools of refuge, creating a “knife edge” of survival for the fish, says fish ecologist Stephanie Carlson.

California’s current drought may forecast their future. “The timing of the fall rains strongly influences their survival,” Carlson says. “Climate models predict that the duration of the dry season will increase. Pools that persist across the summer under current conditions – and provide refuge habitat for the fish – may not persist with a longer dry season.” Vintners and other growers maintain diversion rights on many small central California streams, and their late summer water needs can put further stress on native fish at these sites.

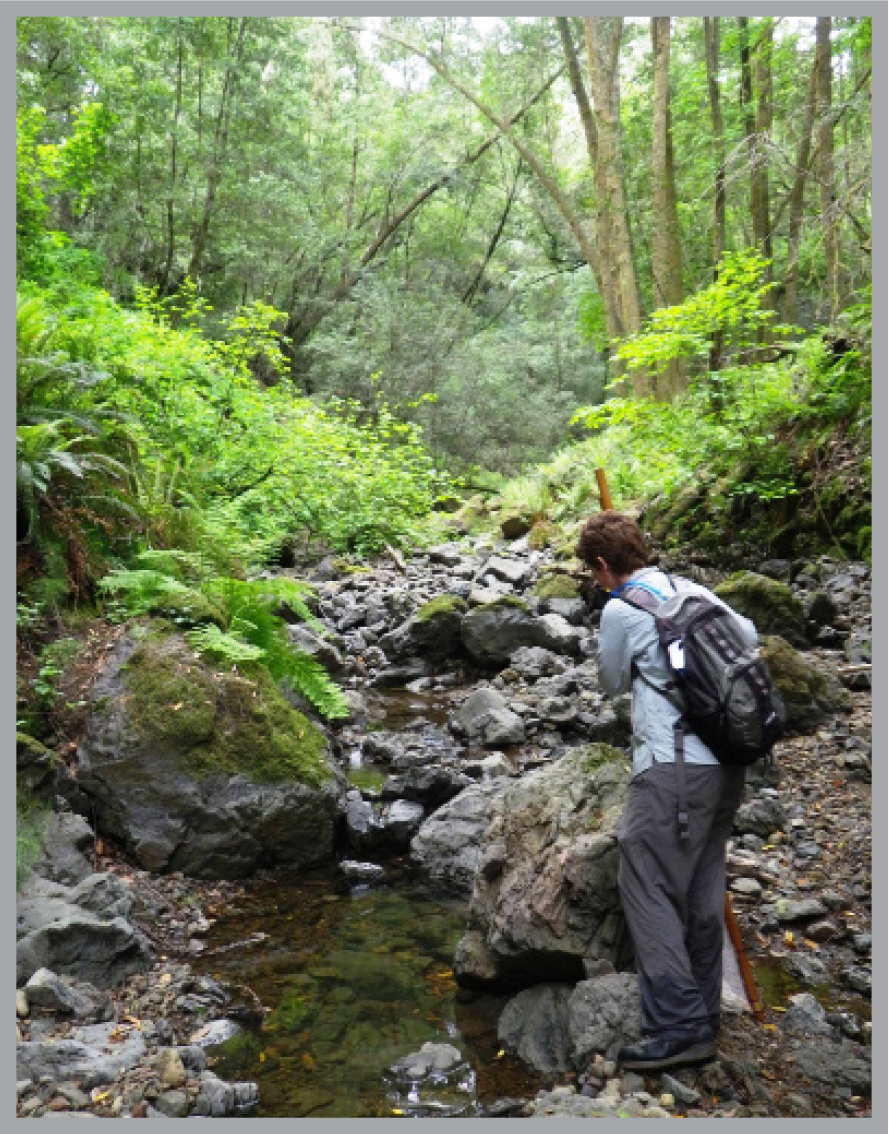

Carlson’s lab group is studying several small salmon streams in West Marin near the towns of Olema and Bolinas. They are trying to determine what water levels are needed to sustain salmon and trout in these waters through the long dry summer. Her research is supported by Berkeley’s Rose Hill Innovator Program which funds novel research in science, math and technology. She will receive $45,000 a year for three years to continue her studies in West Marin watersheds. She also plans to expand the research into even drier regions, including Coyote Creek near Gilroy, where several native fish species are concentrated into shrinking pools during the summer.

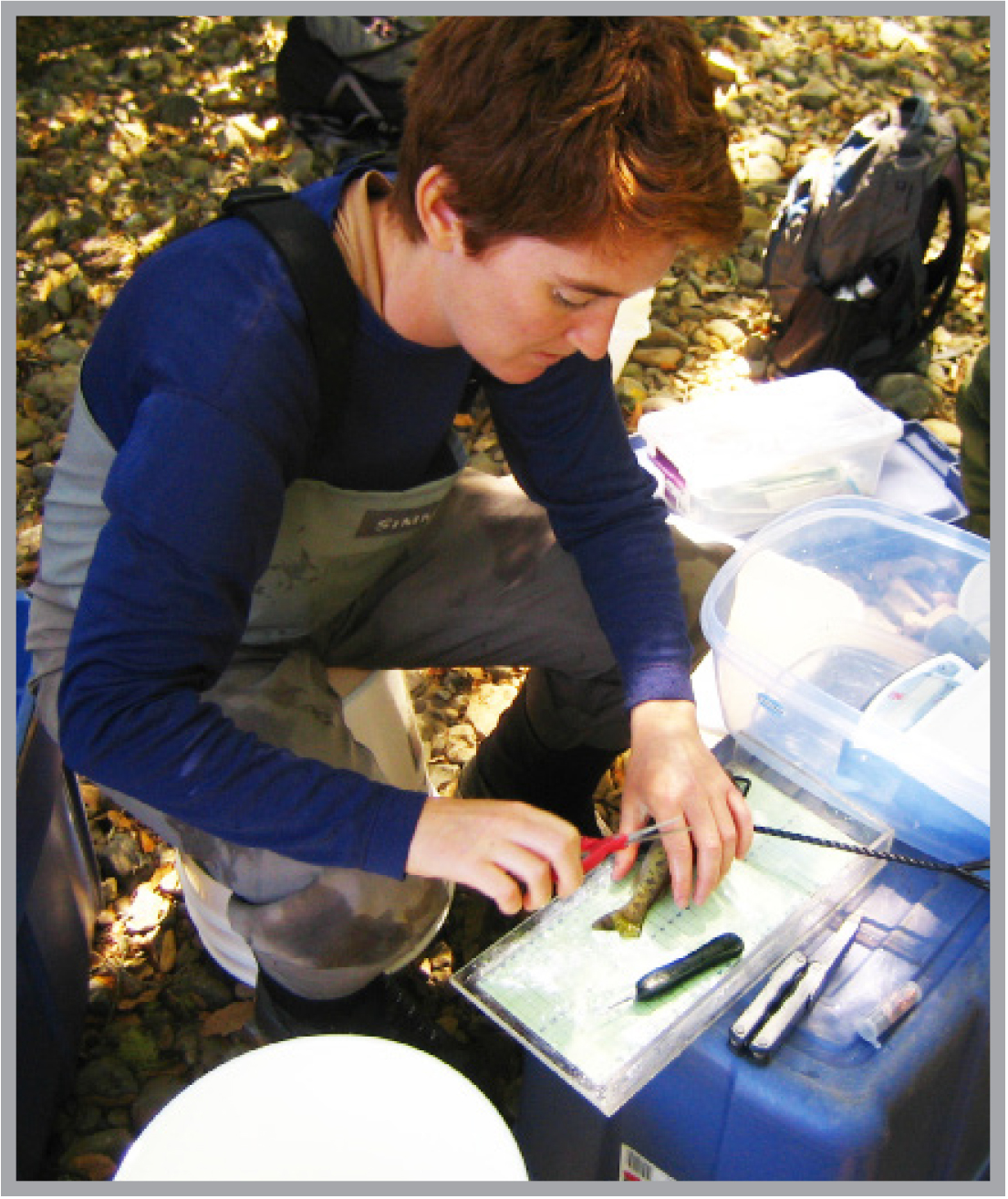

Her population studies begin with an early summer census of two-inch salmon fry in the streams’ deeper pools. She and her students catch the fish in nets or momentarily stun them with electrical currents in the water, an established technique that brings fish to the surface for a few seconds where they are then scooped up in nets. A late summer census establishes how many of the fish have survived the dry season, a presumed bottleneck period for these populations.

A full-length dry suit collapsed on a chair in Carlson’s office suggests just how deep some of the isolated summer pools can get. She dons the suit when pools are so deep that they would otherwise pour into the top of the waders. She also snorkels in pools to study their feeding behavior. “We sometimes snorkel in very shallow streams to count fish, but in other cases, we are in pools that can be over ten feet deep,” she says.

In some studies, she also uses a more high tech strategy that allows her to track the fate of individual fish. At the time of the early summer census, she implants a rice grain-sized transponder in the fish’s body cavity and releases the fish. Returning throughout the summer, she and her students can track population changes by detecting signals from the transponders using a hand-held antenna to pick up the signal.

If she disturbs the water and the source of a signal moves, that’s one fish counted in the census. If the signal source stays in place, that means a dead fish, probably at the pool’s bottom. A signal missing from the previous census probably represents a fish picked off by raccoons or birds.

The young fish appear to minimize predation pressure by holing up in the shaded pools. Her research may clarify just how much water they need – not just to survive predators but to survive at all.

By monitoring fish populations and environmental conditions, Carlson’s research could help state and local water managers balance the water demands on these valuable intermittent streams. Farmers in these coastal watersheds are seeking guidance on how they can modify their diversions to protect the native fish – a concern likely to grow in a changing climate, she says.

“Coho and steelhead have probably relied on these streams for breeding and rearing for thousands of years. We hope our research can help assure their survival into the future while still providing water for other uses.”

_________________________________

The Rose Hills Innovator Program supports distinguished early-career faculty at UC Berkeley interested in developing highly innovative research programs in the fields of science, technology, engineering and math (STEM). The program intends to strengthen the efforts of UC Berkeley’s world-class faculty by providing seed support for projects with exceptionally high scientific promise. For more information, see rosehillsinnovators.berkeley.edu.

Additional Information

Research profile on Stephanie Carlson