Research Expertise and Interest

protein synthesis by the ribosome, RNA, antibiotics, human translation, escherichia coli

Research Description

Human translation

Human bodies are quite complex, with many different cell types and tissues, but only one genome. To put information in our genome into action, the different steps of gene expression must be regulated to lay out our body plan, and to maintain it. We are beginning to appreciate that regulating when and where proteins are made from the messenger RNA (mRNA) copies of our genes is critical for us to develop and stay healthy.

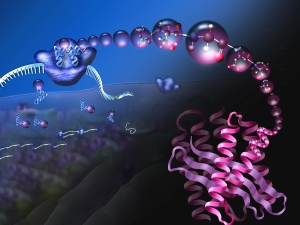

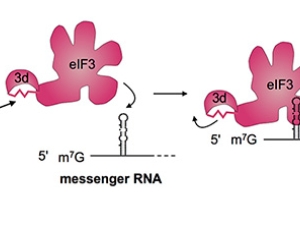

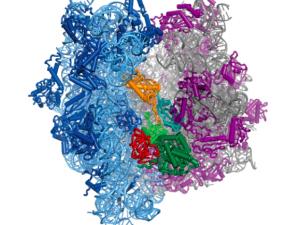

Proteins are polymers, which means protein synthesis–or translation–happens in three overall steps: initiation, elongation, and termination. In all of life, translation initiation is heavily regulated. That's probably because it's better not to start making a protein until it's needed, rather than stopping in the middle of making it. In humans, translation initiation involves many general translation factors, proteins and protein complexes called eukaryotic translation initiation factors or eIFs. We have focused on eIF3, because its large size remains a mystery.

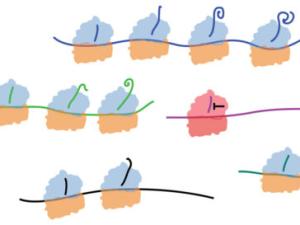

Human eIF3 is targeted by viruses like the hepatitis C virus that highjack translation for their own ends. We think that these viruses are tapping in to specific ways that eIF3 is used in normal human biology. With this idea in mind, we recently discovered that eIF3 is more than a general translation initiation factor. It can activate or repress translation of specific mRNAs that control how cells grow and divide. Notably, a number of these mRNAs encode key proteins involved in cancer. We're now working to understand how eIF3 binds these mRNAs to turn them on or off. We know that RNA structure is likely involved, rather than just a linear sequence pattern. We're also interested to find out if eIF3 regulates other mRNAs in different kinds of cells. To answer these questions, we are using systems biology, biochemistry and structural biology.

Engineered ribosomes

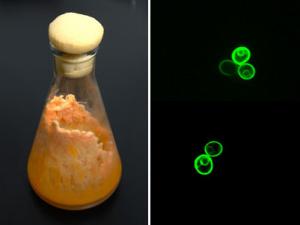

Researchers at Cate Lab are working with the Center for Genetically Encoded Materials about ways to engineer bacterial ribosomes to make new kinds of polymers, rather than proteins. They study how ribosome structure and function can be altered to enable new polymerization chemistry in the ribosome. They are interested in designing screens for new activity, characterizing mutant ribosomes in vitro and with cryo-EM, and in gaining a better understanding of how the ribosome is (and is not) amenable to engineering.